Searching For Movies & People

Hotel Nacional is impressive as you enter its tiled lobby, walk by uniformed hotel workers opening doors for you, stroll through its outdoor gardens with pheasants chilling on the grass, and view the ocean from its cliff top park overlooking the Malecon.

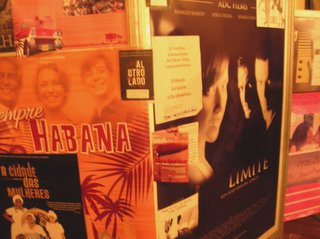

The Hotel was not only the command center for festival coordinators, but it was also the hub for the filmmakers, where they drank mojitos and cubre libres, smoking, chatting, being filmmakers. It was fly, meaning it was cool. It was also like any other film festival where you could tell which projects had money, and financial backing just by the posters, and which ones didn't have any posters at all, and therefore no money. Here's a hint: if you stare long enough, and squint, then magnify the photo of the bullentin board above you'll see our poster for Bloodletting. It's tiny yet creative, and most definitely symbolizes our placement in the festival -- a dark horse. Normally, I dislike the unconscious use of racist, and or biased language that equate words referring to "black" or "dark" with bad and negatives values, but in this case, I think the word "Dark Horse" is positive and appropriate since the definition is that "a dark horse is a bit of a mystery."

Anyway, it was a great festival, the people were nice, not like other festivals where egos abound. Here, everyone shared the crumbs, like pieces of tape to put up their advertisement. Nicole and I shuttled between checking email in the business office, changing money into Cuban Convertibles, checking screening schedules, reading film synopses in the catalogue, and using pay phones to search for people I came back to reconnect with, people who volunteered to help with the doc who I'd met during my first trip to Cuba, but who I had lost contact with over the years it took to complete the project. I thought looking for those people would be easy, especially since a bunch of them were union workers, one of them was a doctor, and another a nurse, both long time healthcare workers. It wasn't.

We began our search in Centro Habana by visiting the CTC, the Confederation of Cuban Workers, the union organization that co-sponsored my first trip with the U.S. Healthcare & Trade Union Committee. While waiting to meet with the Director of International Relations, I was nervous about explaining why it had taken me so many years to finish the documentary. Nicole assured me that she thought the CTC would understand how me not having money slowed everything down. My concern was that the Cubans who had helped me would think less of me, that they would think that the project didn't matter to me becuase it took so long.

I was also concerned that some would think that I was a CIA plant since on my first trip I had overheard a few Cuban healthcare workers wonder aloud if I was videotaping the tour for the U.S. Military and the CIA. Though the idea of me collaborating with the American government is so far-fetched, it made me realize how much pressure Cubans have been living under given that the American government has for years adopted cruel and inhumane policies designed to hurt and destroy the Cuban government, but really the Cuban people. And what most Americans don't know is that there have been more than 60 attempts to kill Fidel Castro, the money for such clandestine operations coming directly from the United States. A definite misuse of American tax dollars.

When we finally met with the CTC Director of International Relations, Manuel Montero Bistilleiro, he barely remembered our delegation because they sponsor so many international trips and it had been 5 years ago. However, when I pulled out the dvd and showed him pictures from the trip he immediately recognized the faces of the coordinators of the U.S. Healthcare & Trade Union Delegation. I thought to myself, now Nicole and I will be able to reconnect with the people who helped, but it was not to be. Manuel was heading to Mexico for an international workers' conference that very day and couldn't help us in our search. Still, he was gracious and kind in seeing us and said he understood how having no money had prevented me from completing the documentary sooner. I was disappointed that he couldn't just pull out a magic file that listed everyone involved in my first trip, but at least I was able to give the CTC a copy of the documentary and thank them officially. Like most Cubans, he was kind and warm, and wished us well.

We then went to Hospital Nacional Hermanos Ameijeiras, the highest building in Centro Habana, and the place where innovative surgical techniques have been developed. Our next step in the search was to try to find Doctor Elsira Fernandez, a pediatrician who is one of the Cuban healthcare workers interviewed. Dr. Fernandez, who was intelligent and very shy when I interviewed her, explained the Cuban nationalized system. During the interview in her apartment off the Malecon she also told me what her life was like before the revolution, and I felt lucky to have been given a view into her personal life.

She admitted that she was a child of campesinos, poor country people, and that she had no chance of becoming anything other than that of a poor farmer, and a poor farmer's wife. She told me that life for the poor country people less than 50 years ago was miserable, and humiliating, especially since most of them were teased, and called guajiros, counutry bumpkins and hicks. Despite the difficulties she said that she and her sister both dreamed of becoming doctors, even though they knew it would never be, that it was unrealistic, that life in pre-revolutionary Cuba had many guarantees, that it was guaranteed that poor people would always remain poor, and that women would always remain uneducated and subject to sexism. When the revolution came and campesinos were offered scholarships to college Elsira and her sister knew that only one of them would be lucky enough to get educated. This caused them much sadness because they knew that the one sister left uneducated would never be able to fulfill her dream. Conflicted but also hopeful, Elsira and her sister both decided to apply for educational scholarships, and when they learned that both of them had been granted the chance to study medicine they felt as if a miracle had happened. 40 years later Dr. Fernandez and her sister are both doctors. Though her personal story was not included in the documentary I've always remembered it because I was impressed that two poor country girls with potential were given opportunities that changed their lives. Imagine what poor kids in the United States could do if we believed in their potential and stopped cutting scholarship programs.

Anyway, back to our search in the hospital, Nicole and I met with a few hospital workers, but none of them knew Dr. Fernandez, and there was no magic file with information referring to her. I remembered that she was nearing retirement age and that she was also working in the Public Relations department, but none of those details helped either. Another dead end. As we sat in the hospital lobby, disappointed and sweaty, and with tired feet, I wondered if I'd be able to reconnect with anyone.

The next person I was desperate to connect with was an AfroCuban nurse we interviewed, Sonia Ruiz Valdez, who worked in a Senior Citizen's Center in Centro Habana. But between looking for her, trying to schedule a trip to visit a Cuban filmmaker I connected with via the internet, and schlepping from our casa particular in Old Havana to Vedado, where the nucleus of the festival was, Nicole and I were exhausted. The photo of her napping in a park is real. She was so tired we had to sit there for at least a half hour, where she snoozed and rested, and where I watched some Cuban Jews having an event at the Casa de Amistad, the House of Friendship. Somewhere between her nap and my frustration we decided we should move closer to the festival. We had no idea it would become our domestic pattern, to continue moving from casa particular to casa particular. So, without that foreknowledge, we packed up our things, and made the move across town to Vedado.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home